Cedar Gallery

Home

|

Cedar info |

News |

Contact |

![]() Dutch

Dutch

Terracotta Army of Xi'an 2008 ©a.wagenvoorde

- - - -

Chinese art, conceived by man's

intelligence, given physical form by man's hands, is for man. It

portrays his image, delineates his aspirations, and exists to express

his holistic wordly experience. In our estimation, this art must be

taken down from museum shelves and walls, and out of books and websites,

and reassembled in the only permissible way - as it relates to the

realities of life at the time it was created.

A hanging scroll on a wall may very well be the only surviving remnant

of a tryptych ( a picture on three panels fixed side by side), a fact

one should remember when considering the quality of it's composition, or

choice of colours. Neolithic painted pottery of the Yang-shao culture is

only decorated from the shoulder up, because the vessels were meant to

be seen from above surrounding the dead. Roof ornaments glimmering over

the treetops beckon pilgrims to come to the temple. They are not

meant to be seen in an exhibition case at eye level, let alone as a

picture on a website.

Even as we relate paintings to walls, sculptures to buildings, or

ceramics, lacquers, and jades to furnitures and furnishings, there is

still the question of how they fit with the architecture: tombs, houses,

palaces, gardens and temples.

Chinese self awareness, has attuned him to his surroundings, in which he

sees order in the physical world. This order is reflected in his art.

The ancient Chinese saw their world without ambiguity: The universe is

considered as a time-space continuum. There is top (= heaven), bottom (=

earth), and there are four directions (east, south, west and north),

plus the past, the present and a future.

In texts of the Chou period (1050 - 256 BC.) inscribed on jars, the four

borders (of this square world) are symbolized, or guarded, by four

fantastic animals: the Blue Dragon of Spring - the beginning of

life for the east, the Red Bird of Summer - the zenith of life for the

south, the White Tiger of Autumn - the harvest and death for the west;

and most intruigingly, not ending with death, a black intertwined form

of a snake and a turtle - two hibernating animals, representing Winter

and the preparation for the life of the next beginning.

Man, the most fantastic animal

of them all, is in the center, facing the Red Bird, fully aware of all

the other animals around him.

Chinese cities often adopt the names of these fantastic animals for

their gates.

When a visual image is full of symbolism, it is like a written page,

transmitting a quantity of information about itself and its maker. The

ceremonial function of ritual bronzes of the Shang and Chou dynasties

indicates that their role in ancestral worship and in spiritual

communication was an important one. Fortunately, these ideograms are

frequently found inscribed on the ritual bronzes themselves. The

composite animal forms seem to represent the combined powers of the

animals depicted. They present themselves as supernatural beings or,

more likely, supernatural powers or forces. It would be naïve to see

these designs of great imagination and visual strength as the simple

composition of animal parts. As these vessels were used in ceremonies

that provided communication between the living and the dead, the motifs

and designs found on these food or wine containers, as well as on

ceremonial weapons, were probably not only for decorative purposes.

The composite animals of the Shang and early Chou periods transitioned

to the Han dynasty (about 200 BC - 220) guardian beasts of the four

directions and even to common animals, domestic and wild. At this time,

plant forms also begin to appear as symbols in art. No longer are human

figures hidden beneath the guise of animal features seeking protection

from the mythical forces. This is the time of the philosophers and a

time of changing psychological outlook. Logical thinking, keen

observation, and analytical attitude toward factual information all help

to reduce fear of the unknown and dim the luster of the mythical symbols.

The concepts

and manifestations of religious India are soon to be introduced to

Chinese man and hisworld, via the vehicle of Buddhism. The

difference between the Indian self-image and that of the Chinese is

considerable, and therefore not easy to combine. In India there was the

concept of god, and the aspiration heavenward. The universe is circular,

requiring the central figure to face all directions. Around this center,

the Indians are lifelong pilgrims forever circumambulating it. In

China, the buddha is enthroned in a palace hall. And the domestic house

transforms itself into a holy place of worship.

The development of figure sculpture and painting under Buddhism was a

glorious page in the history of Chinese art. The sensitivity to relative

positions of objects in a visual composition and the expressive use of

lines are but two prominent examples of this achievement.

The Chinese had not formulated an organized church before the challenge

of Buddhism. Later, in the tenth century, a new visual tradition was

developed to satisfy these spiritual needs. The painting of godlike

mountains in the vigorous landscape traditions of China has its humble

beginnings in the simple backgrounds in Buddhist narrative scenes. It is

an art having roots in China, that enriches the Chinese spiritual

experience; at the same time reinforcing the rational world view, it's

recognition of nature with all its moods and mysteries. As the Chinese

opens his back door to nature, with it's artistic landscape paintings

and garden design, he yearns to provide an arena to express his

intellectual energies. Chinese painting and calligraphy are closely

related. Their objective is not to define, i.e. to describe a flower in

an analytical sense, but instead, it is an attempt to convey 'flowerness'.

************************************************************************* T O P ********************************************************************

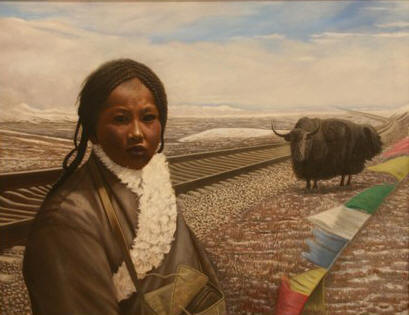

Liu Ye was born in Beijing in 1964, so he came of age

during the Cultural Revolution. This was the period between 1966 and

1976 when all art was at the service of the state and individual

expression was explicitly forbidden.

Liu Ye’s father was a children’s book author, his mother a language

teacher. One afternoon, Liu Ye discovered a collection of none-Chinese

literature books by Lewis Carroll, Hans Christian Andersen, Tolstoy,

and many others. These books were hidden in a chest in the house where

they lived. Although these books were banned at the time, Liu Ye

nonetheless studied their illustrations intensely. Besides, his

grandmother told him fairytales at night, feeding him with stories of

imagination and miracles.

As a young adult, the artist went on to study industrial design and

mural painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, before moving to

Germany to pursue an MFA at the Hochschule der Kunst in Berlin from 1990

to 1994.

Composition with Black, White and Grey, 2008

He later spent time in Amsterdam as an artist-in-residence at the

Rijksakademie, where he first encountered works of art by Mondrian,

Vermeer, Klee, and Dick Bruna.

Regarding his work superficially, they evoke the impression of being

manga-like or just illustration.

His work has been exhibited extensively in China and Germany.

A Composition for Mondrian

************************************************************************* T O P ********************************************************************

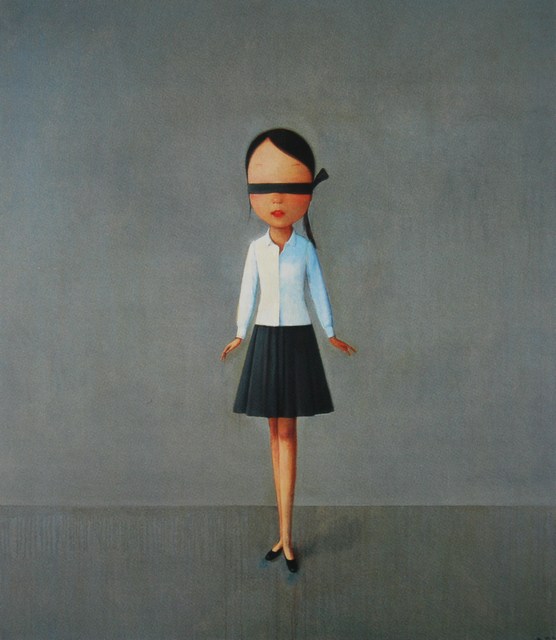

‘I admire the vigour and persistency of miners and I admire the vigour of their children! This vigour means that the human being is only the surface of animals. I just want to question and criticize history and reality.’

Yang Shaobin, who was born in Tangshan, China, in

1963, in the 1990s was one of China’s most representative painters of

contemporary art.

At the beginning of the 90s he participated in the artistic movement

Cynic Realism and Political Pop. The main subject of his works being

Chinese soldiers, policemen and heroes of the Cultural Revolution as

symbols of politics and power, like ‘Life doesn’t rest, the assault

doesn‘t stop’ (1993) etc. These works subverted this historical stage

of China’s common idols by his ironical style, eliminating the holiness

and pathetic feelings and being proof of political consciousness and

taunt meaning.

From 1997 on the main subject of his works is violence, turning his

style into a dark red depiction of brutality.

In his later works of violence the main subject of cruelty is extended

from the individual to international wars, terrorism and related

problems.

Yang Shaobin’s creations of 2005 and later are titled by himself as ‘mixed works’.

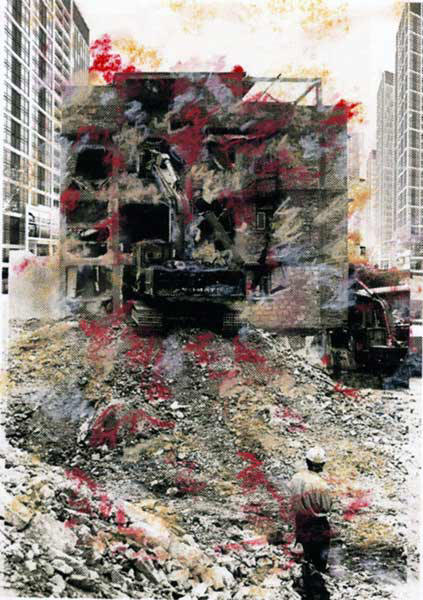

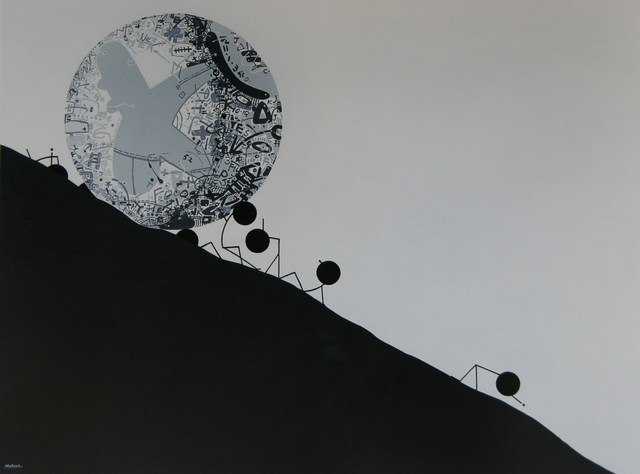

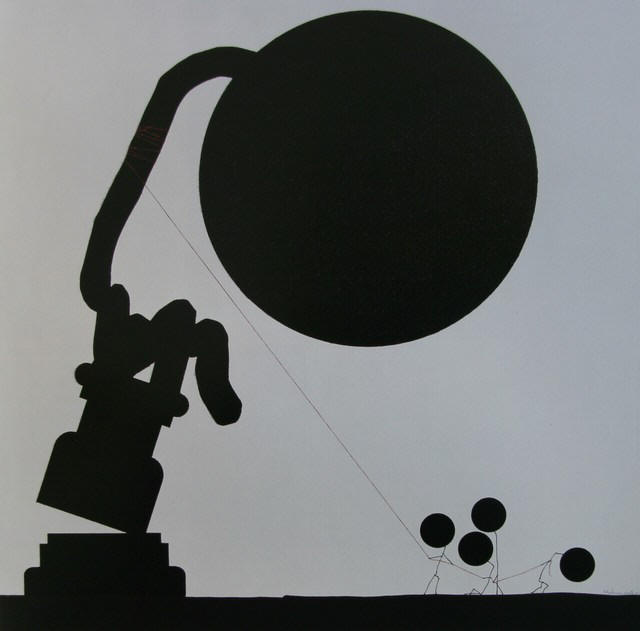

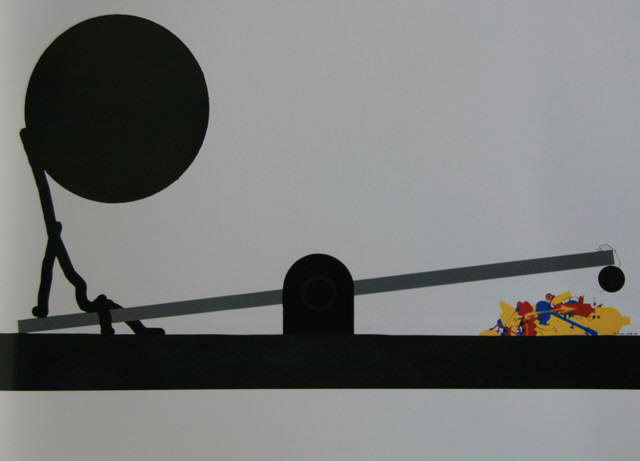

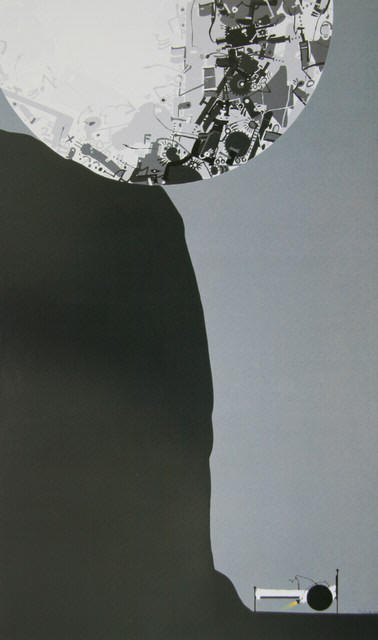

All the paintings shown here are titled: X - Blind Spot +

a number

These are oil paintings, size 194 cm x 357 cm, 2008

X – Blind Spot

Since 2004, Yang Shaobin and the Long March team have

been on the road, working deep in the coalmining communities of rural

China.

The exhibition ‘X – Blind Spot’ is the final showcase of this four year,

two-stage collaboration following ‘800 Meters Under’ which was presented

at Long March Space in September 2006.

For ‘X – Blind Spot’ the team traveled to Chang Zhi, Shuo Zhou and Da Tong in Shanxi Province, extending further to Hebei, Northeastern China and the plains of Mongolia. This collaborative project not only presents the high-tech super-scale environment of open-pit mines, but also the small, home owned operations, provocatively illustrating a particular kind of social geography and urbanization, from micro to macro levels of official and private engagement. Yang Shaobin’s involvement with these human geographies, and his witnessing of the lived consequence of China’s industrial legacy and its corresponding economies, powerfully comes to the fore in these resulting works.

Whereas ‘800 Meters Under’ took darkness as its

frame, exploring the physicality of being underground, ‘X – Blind Spot’

manipulates light and shadow, a visualization of ideas of positive and

negative, white in black black in white. The ‘X’ in the title of the

exhibition refers to the process of x-ray. ‘X’ expresses a caution, a

marked site.

At the same time, ‘Blind Spot’ is a warning, a questioning, an

investigation, and a testimony. This term also refers to the large-scale

mining equipment used in these geographical areas called ‘KOMATSU 170’,

at either end of the machine, there is a blind spot. Within the

boundaries of this ‘blind spot’ is potential ruin.

Such intertextuality has been constructed between project and artist; artist and work; work and reality – these relationships revised, subverted, twisted in a powerful form of self-reflection. In ‘X – Blind Spot’, these interchangeable concepts are mediated through depicting peripheral action. The present and absent qualities of Yang Shaobin’s artistic x-ray expose his own development of light, these works acting as personal filter, offering perhaps another kind of visual ‘blind spot’.

©PAM PHOTOS

************************************************************************* T O P ********************************************************************

From the very First Emperor to

political leader Mao Zedong in 1976, the mausoleums built for the rulers

played an important role in Chinese society and ancient Chinese

architecture. The landscape around the city of Xi'an, in the province of

Shaanxi, is characterized by many old burial mounds that bear witness to

the link with empires from a distant past: they mark the underworld of

the ancient emperors. In an almost literal sense these emperors took

their worldly realm with them to the afterlife. A mausoleum was a palace

for eternity that had to be laid out with rooms and objects that were

worthy of this function, and enabling it in practical terms. The

mausoleum of the First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huangdi, is an example

of a tomb from the late 3rd century BC where terracotta figures

and traces of human sacrifices have been found. This burial complex is

primarily known for the discovery of thousands of life-size soldiers, "a

Terracotta Army".

The Western Han dynasty (206 BC to 9 AD) witnessed a peak in imperial

enthusiasm for buildings tombs. To accompany Emperor Jingdi to the

afterlife, more than forty thousand terracotta statues formed his

terracotta army and court. Livestock and other animals are also

represented.

The first photos below are from an exhibition in Assen, Holland (2008). © c and a wagenvoorde

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The pictures below are taken in Xi'an, China, in

2009

©PAM PHOTOS

************************************************************************* T O P ********************************************************************

The Zhou Brothers are contemporary Chinese artists,

renowned for their unique collaborative work process. They always work

together on their paintings, performances, sculptures, and prints, often

communicating without words in a so-called dream dialogue. Their

thinking, aesthetic, and creativity are a symbiosis of Eastern and

Western philosophy, art, and literature that informed their development

since early childhood.

The Zhou Brothers, Shan Zuo and DaHuang Zhou, were born in China 1952

and 1957 respectively. They studied drama and painting at the University

of Shanghai from 1978 to 1982 and the National Academy for Arts and

Crafts in Beijing from 1983 to 1984 where they received their MFAs.

During the beginning of the 1980s they became leaders of the

contemporary art movement in China. In 1985 they won the National Prize

of the Chinese Avant-Garde of the Ministry of Culture and the Prize for

Creativity from the Peace Corps of the United Nations. They were also

honored as the first contemporary artists ever to show their work in an

exhibition that traveled to the five largest museums in China, including

the National Art Museum of China in Beijing and the art museums in

Shanghai and Nanjing.

Realizing that the political and cultural landscape at that time would not allow them to expand their careers, an invitation to exhibit in Chicago in 1986 presented a timely opportunity to make the transition onto an international stage. The Zhou Brothers have consequently maintained their home and studios in Chicago while actively exhibiting their work nationally and abroad. They have held guest professorships at the International Academy for Art and Design at the Fachhochschule in Hamburg, Germany, 1996 and at the Sommerakademie in Salzburg, Austria, from 1996 to today. They received one of the most prestigious fine art awards, the Prize of the Haitland Foundation, Germany, 1996. The most important demonstration of their collaboration is the performance the Zhou Brothers gave during the opening ceremony of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in 2000. In front of the most important political, economic, and cultural leaders in the world, they created a large-format painting titled New Beginnings to give due treatment to their most important theme, humankind.

Ballet dancer, Shan Zuo (1952) and Da Huang Zhou (1957)

©PAM PHOTOS

************************************************************************* T O P ********************************************************************

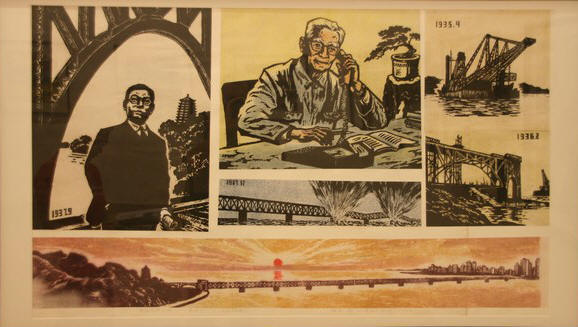

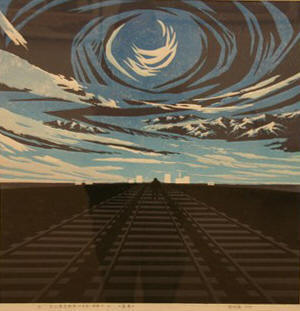

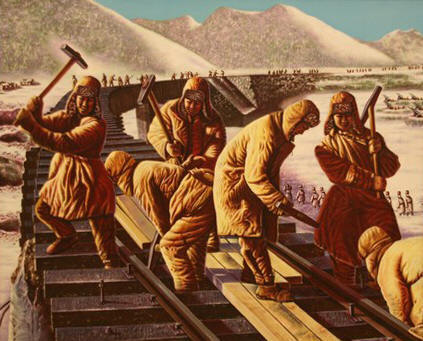

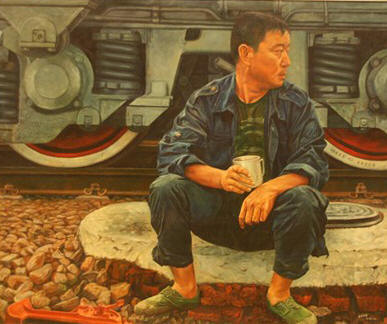

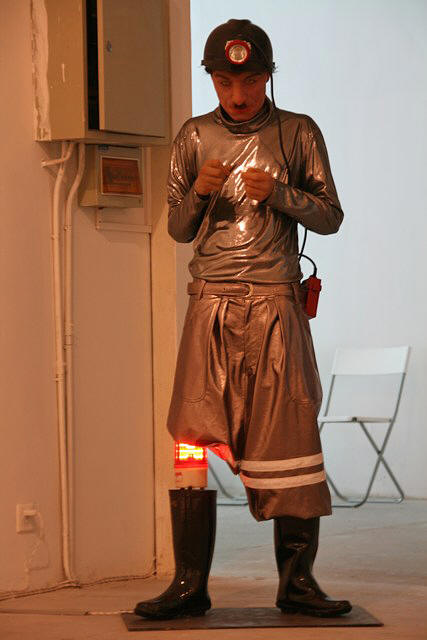

September 2008

In memory of the 30th

anniversary of reform and opening-up, and the 60 anniversary of the

establishment of China's Railway Construction Corporation, the 14th

Highway Painting Exhibition, with the theme of "China Railway

Construction and China railways" was held in the National Art Museum of

China on September 2008. The following is an excerpt from the museum's

description of this event.

"Works of this exhibition will show overwhelming development history

of China's railways in a century comprehensively and systematically

through three main periods of 'the past, the prersent, and the future'.

Wherein, works with a thick feeling of history created with themes of

influential events and persons from starting railway construction in our

country to the end of the 20th Century is 1/5 of 'the past' period.

Works of 'the present' period, which cover 3/5 of all the works, are

created focusing on the themes of construction of high speed railways,

the Olympic Project and key projects both at home and abroad in 30 years

since the reform and opening-up. The works of 'the future' period, which

cover 1/5 of all the works, mainly take expectation of developing

direction of railway construction in the future show future development

of railway construction in China in looking forward, with modern

representing way."

As all the further information was in Chinese, we can't inform you about the painter or the title of the painting. All information is welcome!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

©PAM PHOTOS

************************************************************************* T O P ********************************************************************

Ai Weiwei (1957)

‘Since his emergence as an artist in the late 1970s.

Ai Weiwei has been a prime mover in the Beijing art scene, combining his

roles as artist, architect, and instigator to create new institutions as

well as new art forms.

……

Ai Weiwei grew up well aware of the irrationality of political movements

and social upheavals.

His family returned to Beijing in 1978, where he attended the Beijing

Film Institute and helped organize ‘The Star’ group, the first artist

collective to present avant-garde art in China.

In 1981, he moved to the United States, where he immersed himself in

experimental art movements, from Dadaism and Fluxus through Andy Warhol

and the East Village scene, beginning to incorporate these ideas into

his work.’

From: China Art Book, Ai Weiwei

When Ai Weiwei returned to China, in 1993, he soon

became a central figure in Beijing’s East Village.

In 2000, on the occasion of the Shanghai Biennial, Ai Weiwei arranged

‘Fuck Off!’, with critical and disturbing art works.

By then he was gaining international attention for his own art works

which meld a Dada sensibility with traditional Chinese antiquities and

craftsmanship.

Ai Weiwei is active in sculpture, installation, architecture,

photography, film, and social, political and cultural criticism. Ai

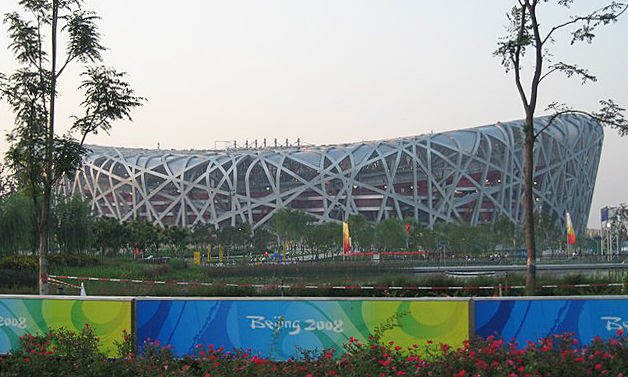

collaborated with Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron as the artistic

consultant on the Beijing National Stadium for the 2008 Olympics.

As a political activist, he has been highly and openly critical of the

Chinese Government's stance on democracy and human rights.

5000 kg Sunflower Seeds 2010

Sunflower Seeds is made up

of millions of small sculptures, apparently identical, but each one

actually sculpted and painted. These are two smaller versions of the

work which, on having its debut in Tate Modern in 2010, made Ai Weiwei

known to a wider audience.

To the Chinese people, sunflower seeds have various connotations. Not

only do they serve as food: during the Cultural Revolution, they

acquired symbolic meaning as well. Once Chairman Mao had appropriated

the sun as his personal symbol, the Chinese people were compared to

sunflowers, which looked up in admiration at The Great Helmsman.

These thousands of seeds, which Fuse into a single grey carpet in the exhibition, are made of porcelain however. That fact gives rise to another image: that of 1600 workers in Jingdezhen (China’s porcelain capital) who spent an entire year producing the millions of tiny forms by hand and turning them into sunflower seeds with a few grey brushstrokes.

Tree #2 2011

hout/wood

Rocks 2009-2010

porselein/porcelain

These porcelain and wooden sculptures were executed using ancient handcraft traditions. The ceramic stones were made in Jingdezhen, where Chinese porcelain production originates. The two tress have been built from fallen trunks collected in the mountainous regions of southern China. Similar to the construction of Ai Weiwei’s previous wood sculptures, the tree fragments have been interlocked using a classic Chinese technique.

Combining natural and crafted elements, the installation calls to mind a

traditional Chinese garden, a place to meditate. At the same time,

however, one may feel slightly disconcerted.

Forever 2003

42 bicycles

The allusion to China as a distinct nation of bicyclists is right at hand, linking in to the understanding of China as a distinct mass society. The bicycles in Forever are identical and connected in one big overall structure in a way so that the individual bicycle could not be separated from the whole without destroying the whole.

In its composition, the construction merges a complex, helter-skelter tangle of bicycle parts with a simple and light expression. In that sense, the work could be said to anticipate Ai’s best known architectural work, the Olympic Stadium in Beijing, popularly known as the ‘Bird’s Nest’.

Fountain of Light 2005

All pictures: ©PAM PHOTOS

More about Ai Weiwei: http://www.cedargallery.nl/engother_artists.htm

************************************************************************* T O P ********************************************************************

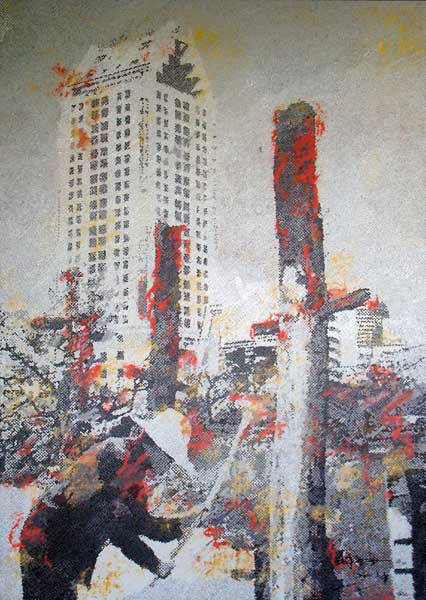

Xie Guoping is on the vanguard of a new artistic vision in Chinese contemporary art. His technical virtuosity and the emotional intensity of his painting belie his youth. Born in 1985 to a farming family in the small town of Wuxi ( near Chongqing), he graduated from the Sichuan Academy of Fine Art in 2007, and his entries in the graduation show already began attracting attention. Drawing from his own observations of daily life and some surprising stylistic influences, Xie carefully and quietly draws us into his engaging, individual idiom.

Approaching me, 2008

Working in acrylic on canvas, Xie uses monochrome dots on a large scale to evoke a photojournalistic mood. The approach may remind viewers of the Ben-Day dot compositions of Sigmar Polke ( http://poulwebb.blogspot.nl/2011/04/sigmar-polke-part-1.html ) and Roy Lichtenstein, but it is not Xie's intention to make a similar Post-Modernist commentary on mass media. Recalling Polke's work, Xie's pieces are challenging to decipher at close distance but become increasingly legible as the viewer steps back from the image. Polke used this effect to subvert commercialised sexuality (as in his 1966 Bunnies http://www.flickr.com/photos/dctwinkie5500/5449361338/ ), but Xie employs it to invoke objectivity and, at times, to edify the ostensibly insignificant or mundane.

Dead Tree Memory, 2009

In Red Gate Gallery, Beijing, No Trace was organised, his first solo exhibition. It was dominated by works he painted in the aftermath of the May 12, 2008 Sichuan earthquake. The pieces depict the destruction, damage assessment and cleanup. His vignettes portray the ordinary people, the workers going about their lives in the wake of the tragedy. Whereas many artists might take the opportunity to focus on drama or sentimentality, Xie wishes to draw our attention to the unnoticed details and the unsung heroes.

On the Scene, 2008

Providing an effective counterpoint to Xie's photojournalistic

objectivity is his captivating overlay of painterly abstractions. He

finishes each piece with swaths of fiery colour, usually red or yellow.

These gestural flourishes animate the subject matter and inject Xie's

personal subjectivity into the work. According to Xie, the autumnal

palette he uses in these fields is inspired by several of the painters

in the Nabisme movement, such as Edouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard.

The Nabis were a self-inaugurated group of artists in Paris in the 1880s

that was not bound together by a particular style but rather by a

commitment to separate, individual artistic visions.

Ten Heroes, 2008

Ten Suns, 2009

Source: ©Red Gate Gallery (

http://www.redgategallery.com )

We express our gratitude to Brian Wallace and Tally Beck

More pictures:

http://www.redgategallery.com/calendar/no-trace-xie-guopings-first-solo-exhibition09

************************************************************************* T O P ********************************************************************

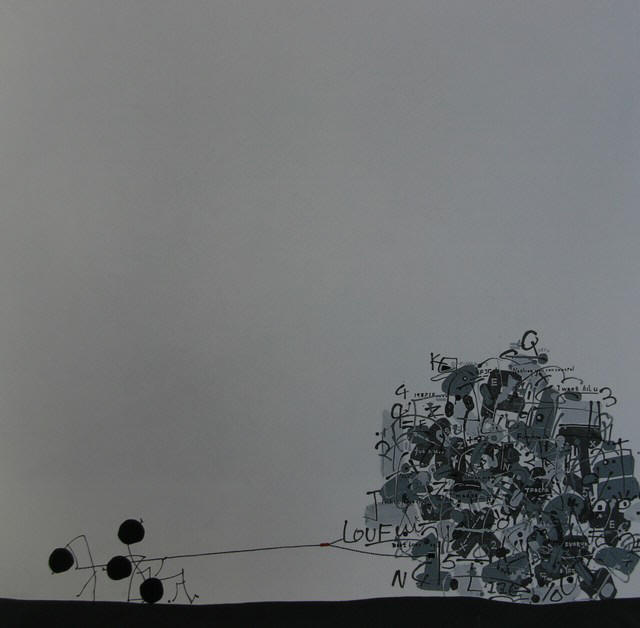

Hu Hua

and his 'Funny Art'

Baggage, 2005

When we

take a look at Hu Hua's works, we start with considering it as

amusing and easy. The works are filled with one or more objects, and

what is noticeable is a tiny 'human' figure, in the form of a

capitalized Q. The elements that Chinese people, but also Europeans or

Americans for example, see in these works, look familiar. It can be a

lamp, a bed or pipelines.

What does the funny Q-shaped figure stand for? Hu Hua once said that his

art concentrates on the self, the human race and the problems that they

are facing.

Endless Life, 2005

People often use great, famous figures of legends and mythology to

identify themselves or their art with. Narcissus or Narcissism seems to

be one of the symbols of the modern age in China. The artists create a

legendary image for themselves and turn into their ideal image of the

self, showing how much they are focused on the 'self', 'narcissism' and

'me'.

On the one hand, it might be based on generalized nihilistic social

values and belief, which seems to be the result of the rising consumer

society and hedonism, disappearing ideology orientation, diminished

sense of social responsibility; on the other hand, it probably arises

from the fact that particular the only-child generation becomes more and

more individualistic, egoistic and individualized. They are eager for

self release, independence and their own powerful voice.

Therefore, creation of the ideal images and concern of the self become

typical of the art by the only child generation (those born after the

80s, in particular).

These features are represented in Hu Hua's works. They are, without

exception, vivid examples of the artist's concern of the reality of the

individual and the self. What is more, Hu Hua's works are reflections

upon the human race (such as belief, civilization, happiness, desire,

etc.), their ultimate values and their relation to nature and the

universe.

Seeking, 2007

As an

artist with a typical academic background, Hu Hua is in constant pursuit

of a free and creative personality, which leads to a search for a more

individualistic and original language for painting. Which leads to his

own 'funny'art.

It corresponds exactly with the features and needs of modern society.

There are several contributing factors. In the first place, symbolic and

codified information become a more direct and effective means of

reception in a world of digital information. Then, the hectic and

stressful modern life is putting man into isolation and alienation, and

he finds himself enveloped by pressure of life, disorientation, escape,

loneliness, sense of diminution and seclusion.

What is free, light, imaginary and humorous is more than welcome. Again,

the playful feature of modern society leads to playful way of life and

social atmosphere, and therefore the corresponding state of mind of

playing while living or living while playing. The artistic creation and

charm seem to combine everything in a playful, reflective and

lighthearted tableau.

Hu Hua's works discuss such themes as the self, the human race and the

universe by employing simple, lovely and interesting language and the

technique of black humour. Such humorous treatment and creation of signs

indicate, that all the values and 'significance' in our age are in an

ongoing inevitable transformation.

Lastly, the choice of cold colors as the principal tone seems to echo

the generalized nihilistic social values and belief.

Liberate Iraq, 2007

Receding Childhood, 2008

Happiness arrives, 2008

Pictures

©PAM PHOTOS

(pictures of an exhibition in newageartgallery beijing, in 2008.)

We are grateful to Guo Jin and Xia Yun for their

information about the artist and his work.

http://www.newageartgallery.com/infogallery-en-bj.html

************************************************************************* T O P ********************************************************************

One of our primary goals at Cedar Gallery is to provide a public forum for both unknown and established Chinese artists to showcase their works. We particularly encourage contributions from aspiring modern artists, but are happy to consider all submissions.

Please, send your contributions to: cedars@live.nl , mentioning 'China, art and culture'.

![]()

![]()