|

Artists

Architecture

Poems

Photography

Quotes

Religion

Stories

Themes

China

Japan

Russia

|

Court ranking system Culture

Glossary

Kimono

Modern Art

Prints Religious

Art

Society

Tenno

Court ranking system

The eight court

ranks conferred on the officials according to the importance of the

posts they held in the Council of State were as follows:

Chancellor

(Number of persons: 1, Court Rank: first)

|

Minister of the Left (1, second) |

Minister of the Right (1, second) |

|

Great Councilors (4, third) |

Minor Councilors (4, third) |

|

Controllers of Four Departments of

Central Affairs, Ceremonial, Civil Administration, Popular

Affairs (4, fourth) |

Controllers of Four Departments of Military Affairs, Justice,

Treasury, Royal Household (4, fourth) |

|

Vice-Controllers (4, fifth) |

Vice-Controllers (4, fifth) |

|

Secretaries (4, sixth) |

Secretaries (4, sixth) |

|

Minor Secretaries (4, seventh) |

Minor Secretaries (4, seventh) |

|

Recorders (4, eighth) |

Recorders (4, eighth) |

The third court rank and above were constituted as peerage. In the case

of the university under the control of the Department of Ceremonial, the

president and professors of literature held the fifth; professors of

Chinese classics held the sixth; professors of Chinese pronunciation,

calligraphy and mathematics held the seventh.

The holders of these ranks were granted stipends.

Everyone who can explain more, or add something interesting about

this item, please, send it to:

cedars@live.nl

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Culture

The Takarazuka Revue

The Takarazuka Revue is a Japanese all-female musical

Theater in the city of Takarazuka, Japan. Women play both male and

female roles in lavish productions, often Western-style musicals, but

always with strong Japanese elements.

The all-female Takarazuka Revue Company touches something deep in the

Japanese psyche, or at least the female Japanese psyche. Many of the

fans are female and most of them are young. And the stars they adore

most are the otokoyaku, the actresses who play the male parts. In

Japan's male-dominated society the otokoyaku represent a vicarious way

for young women to live out fantasies of strength and power. But what

they really come for is romance, the pure, old-fashioned, fairy-tale

variety. So Takarazuka gives them just that, nice stories full of

romance and spectacle but devoid of crudity or passion.

The company is made up of hundreds of members that put on performances

across the country and abroad year-round. Thousands more teenage girls

apply to join every year but the Takarazuka Music School takes on only

40 to 50 new students a year. Those lucky enough to get in face two

years of strict discipline and rigorous training. After their first year

of training, students choose whether they want to be an otokoyaku or

musumeyaku (female role). Again competition is fierce, with factors like

height, build and voice playing a large part. Once training is complete,

students graduate and join one of the troupes.

Every year, each troupe does one run in the company's home city of

Takarazuka, near Osaka, and one in Tokyo. The rest of the year, they

play other theaters around the country or tour abroad. Though Takarazuka

incorporates many elements of western theater, it retains strong

Japanese elements. The epitome of the Takarazuka show is The Rose of

Versailles. It's the story of Oscar, a girl who is brought up as a boy

in 18th-century France, but it comes not from a romantic French novel or

play but a Japanese manga. The company's structure and the school's

training regimen strictly follow the sempai-kohai (senior-junior)

relationship that forms the core of many Japanese institutions,

including those in sports and business.

Takarazuka was founded in the city of the same name

in 1913 by Kobayashi Ichizô, the president of Hankyu Railways. The city

was the terminus of a Hankyu line from Osaka and famous for its hot

springs. To boost both travel on the line and business in the city,

Kobayashi decided to take advantage of the public's increasing interest

in Western song-and-dance shows but with a cast of young, unmarried

girls of unquestionable virtue. In a country that even until recently

frowned on kissing in public, such scenes - implied rather than acted

out - between two girls was deemed more or less acceptable. By 1924, the

company had become popular enough to get its own

theater.

More about the Takarazuka music school.

There is a two-year Takarazuka music school at

Takarazuka city in the west of Tokyo. Girls of 15 - 18 years old are

allowed to take an entrance examination for the music school. Every year

40 girls enter this school and receive education and training for two

years. After having finished this two-years course, they are scheduled

to join the Takarazuka dancing team.

The girls in the school are called "Takara-sienne".

The Takarazuka dancing team and their school started in 1913 and

continued their activity until 1945, the end of the second world war. It

started from the ruins again in 1946, one year after the end of the war.

The repertoire of their dance and musical drama performances are wide,

from traditional Japanese to Western ones. After the war, the Takarazuka

attracted young girls' hearts. But when people started to watch TVs,

they did not come to the Takarazuka theaters - one in Tokyo and the

other in Takarazuka city- anymore. It was a time of crisis for

them.

The managing director came up with a new idea. He

thought that they should perform musical dramas composed and based on

animes or mangas which young girls were reading at the time.

One of the most popular mangas was "The Rose of

Versailles".

It is a story about two officers of the body guard

corps of the Princess Marie-Antoinette.

One officer is a young man, and the other a young woman.The woman has

been raised as a boy from her childhood because her father was an

aristocrat and wanted his son to be one of the bodyguard corps for the

King in the Palace. But contrary to his expectation, the newborn baby

was a girl. Then, the father raised the baby girl as a boy in order that

she should be able to become an officer of the bodyguard corps. It is a

love story of two persons, a young officer and a young female officer.

The French revolution broke out, which caused a drastic change for their

lives...

S.Y.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Hino Tomiko (1440-1496)

Tomiko was the daughter of Hino Shigemasa, born in

Yamashiro province. She became the wife of the 8th Shogun (= the emperor

or the king) Ashikaga Yoshimasa at age 16 in 1455. She had her first

child on the ninth day of the first month of 1459, the child died the

same day however. Unlike her passive husband, who had very little

interest in political affairs, Tomiko was savvy and manipulative, and

placed the blame for the child's death on the wet-nurse, Imamairi no

Tsubone, whom she exiled to Oki island on lake Biwa (Imamairi no Tsubone

committed suicide on the way).

By the mid 1460's, Yoshimasa had decided that he

didn't want to be bothered with the duties of office and decided to

rescind his position of Shogun. However, as Tomiko had not born him a

male heir, he convinced his younger brother, Ashikaga Yoshimi, to first

assist him in office, and then gradually claim the title of Shogun.

Tomiko was averse to this, but at the time had no leverage to contest

the appointment, until a year later, when she gave birth to the future

Ashikaga Yoshihisa. With her standing in the Hino family, and backed by

Yamana Sozen, two factions developed in the capital, one faction

supporting the newly appointed Shogun, Yoshimi, and the other supporting

the succession of Yoshihisa. Thus, this desire of lady Tomiko to place

her son in line for the succession led eventually to conflict in the

land, and the Onin War began.

In the feudal ages, there were two heads, that is,

the Shogun ( the emperor or the king ) who had an actual

political and military power, and the Tenno who had no actual

power.

The Shogun became the Shogun only when he was appointed or approved by

the Tenno.

No one obeyed the Shogun unless he should be approved by the Tenno. On

the other hand, the Tenno had no actual power so he and his family were

supported by the Shogun. One could not stand without the other.

There were aristocratic people called “Kuge” or “Kizoku” who were

positioned under the Tenno and supported him. On the other hand, there

were feudal lords under the Shogun. The feudal lords obeyed the Shogun’s

orders and paid taxes to the Shogun. There are a lot of warriors called

“Samurai” under the feudal lord. In old feudal society, people wore

different clothes and hats, and had different hair styles according to

the social ranks they belonged to. Only the Shogun and feudal lords were

allowed to wear clothes and hats that aristocratic people wore. Common

Samurais wore different clothes and hats.

In the Hino

family, there

were two

daughters. The

elder daughter

became blind

after having a

disease with

high fever. So,

the younger

daughter, Tomiko,

was determined

to be married to

the prince

instead of her

elder sister.

The blind

daughter ( a

little girl in

white clothes )

was sent to a

Buddhist temple

accompanied by a

monk to be a

Buddhist nun.

Below some

pictures of a

movie about Hino

Tomiko.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

O-Waraji

This pair of

huge traditional

straw sandals

called 'O-Waraji'

has been made by

800 citizens of

Murayama City,

in a month. O-waraji

is made of straw

and 2500

kilograms in

weight, 4,5

meters high.

They are the

charm against

evils, they are

symbolic of the

power of 'Ni-Ou'.

Wishing for

being good

walkers, many

people will

touch this 'O-waraji'.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

SOCIETY

Life Cycle

Infancy

One month after birth the Japanese child may be taken to a local

Shinto shrine to be introduced to the guardian gods and symbolically to

all of society.

This is called ‘miyamairi’. Parents and grandparents

bring the child to the shrine, to express gratitude to the deities for

the birth of a baby and have a shrine priest pray for his or her health

and happiness.

Today, most Miyamairi are practiced between one month or 100 days after

birth. In famous and busy shrines, the ceremony is held every hour,

often during weekends. A group of a dozen babies and their families are

usually brought in the hall, one group after another. Before the altar,

a Shinto priest wearing a costume and headgear appears between the group

and the altar, reciting a prayer and swinging a tamagushi right and

left.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tamagushi

During the prayer, the priest cites the name of the baby, the names of

the parents, the family's address, and the baby's birthday. Afterwards,

the parents and grandparents come forward, one by one, bow to the altar,

and place tamagushis upon it.

At the end of the ceremony, rice wine in a red wooden cup is given to

each person in attendance; small gifts are often given to the family.

Annual celebrations for children occur on 3 March for girls (Doll

Festival), on 5 May for boys (Chidern's Day) and on 15 November for

girls aged three and seven and boys aged three and five. This is called

Shichigosan.

Childhood

Under the modern school system in Japan the most important rites of

passage are school enrollment and graduation. The nine years of

compulsory education comprise six years of elementary school and three

years of middle school.

Children who turn six year old by April 1st each year are enrolled

in elementary school, and start their school career by participating in

an enrollment ceremony.

The Japanese educational system

was reformed after World War II. The old system was changed to a 6-3-3-4

system (6 years of elementary school, 3 years of junior high school, 3

years of senior high school and 4 years of University) with reference to

the American system.

Japan has one of the world's best-educated populations, with 100%

enrollment in compulsory grades and zero illiteracy. While not

compulsory, high school (koukou) enrollment is over 96% nationwide and

nearly 100% in the cities.

About 46% of all high school graduates go on to university or junior

college.

The Ministry of Education closely supervises curriculum, textbooks,

classes and maintains a uniform level of education throughout the

country. As a result, a high standard of education is possible.

DEATH IN JAPAN

(1)

Pampas grass, now dry,

once bent this way

and that.

Shoro, died in 1894

A majority of Japanese now feel that the modern

biomedical and technological innovations pertaining to human life and

death have been forcing a change in their common understanding of what,

historically, was the natural way of death and dying. The meaning of

death and the dying process is changing as have the traditional criteria

for determining death, namely, cessation of heartbeat and respiration.

An individual's death should be a personal and

private matter as well as a familial, communal, and social matter.

That’s the way it has been for many thousands of years in Japanese

society and culture.

The ideas expressed in Zen-Buddhist phrases such as "accept death as it

is" and "life-death as one phenomenon" have been key motifs that were

integrated into the traditional Japanese understanding of life.

However, the traditional perception of death as an

acceptable process has been vanishing as the Japanese have applied

modern biomedical technologies more frequently in well-equipped hospital

settings. Although the involvement of family members in the process of

dying and particularly in the death event continues in a variety of

ways, the care of dying patients in Japan is becoming much more similar

to that in many countries of the world. Now, in Japan, a majority of

people end their lives in the hospital, surrounded by high-technology

machine. It is not what most people want. Many, if asked, said they

would prefer to die at home.

In addition, there has been a tradition of not

explaining to terminally ill people the true nature of their condition,

on the grounds that this is the most appropriate way to proceed.

However, views on this matter are changing as well. There is a gradual

move toward telling patients the truth. Many people in Japan say, that

they want to be informed about the full diagnostic information about

themselves/their illness. Nevertheless, a minority of the people say

they would definitely be prepared to disclose such

information to a family member.

Death in Japan… Times are changing.

Inhale, exhale

Forward, back

Living, dying:

Arrows, let flown each to each

Meet midway and slice

The void in aimless flight --

Thus I return to the source.

Gesshu Soko, died in1696

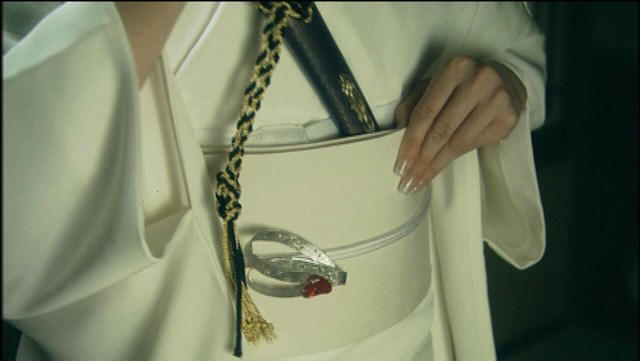

Death costume

In Japan there is a tradition that people still

observe in modern days. It may be rooted in an ancient myth or

superstition. When someone has died, he has to walk on a long narrow

road, a path leading to Heaven. However, during his journey on the path,

many evil spirits appear and allure him to Hell. He has to fight against

such evil spirits so that he may

not go astray.

So, even today, when someone has died, their family puts a small sword

or a knife on the dead body in the coffin. With this weapon, the dead

person can fight evil spirits. The dead person wears a white costume.

This custom has been preserved, even in today's Japan.

In funerals, men and women wear black clothes for such occasions. In the

pictures here, an actress wears a white death costume. It is very rare for

a woman to wear a white death costume while alive.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

DEATH IN JAPAN (2)

Coming, all is clear, no doubt about it.

Going, all is clear, without a doubt.

What, then, is all?

Hosshin, 13th century

A Japanese funeral takes place in three stages, spread over a

couple of days.

The first is the otsuya, literally "transit evening", a kind of wake.

People arrive at a designated place (announced in the newspaper

obituaries), and pay their respects to the departed.

If you want to pay your respects, you must kneel on a cushion, take three pinches of

incense from the fuel urn, hold each one up to your face, and place it

in the incense burner. Afterwards you put your fingers together in a

bowing- prayer. Then, you take a stick of incense from a nearby

box, light it with one of the candles and fan the flame with your

hand to extinguish it. (Never blow on anything at a Japanese funeral.

The breath is considered to be impure.)

With your hand, fan the incense fumes toward your

body, as the smoke is said to have a purifying effect, warding off any

wandering spirits.

The second stage is the ososhiki, the funeral

ceremony itself, held in a hall. There, there are knee-high tables, covered in

cloth. Behind the tables are white flowers, neatly arranged, and

a coffin with a picture of the deceased on

top.

It is not only a funeral ceremony, where people come to pay honor to the

deceased. It has a practical side as well. The persons

present pay a certain amount for the funeral.

The third stage consists of going to the kasoba,

or crematorium

Those who have watched the film "Cherry Blossoms" will have come away

with an impression of what this part of the funeral is like. With (in our view)

a lack of

ceremony, the coffin is pushed into the oven and the door closed. The

visitors bow and say goodbye.

At a specified time, a signal alerts mourners to go to another room. In

this room are to be found the bones of the deceased. The immediate

family takes up chopsticks and places the bones of their beloved into an

urn. Others can also take part.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

KIMONO

There are many types of Kimonos, some are formal and

expensive. Others are casual and not expensive.

Cheap Kimonos are made in factories. But formal Kimonos of high quality

are made by human hands. Each one is different from others.

In Japan, hand-made products are highly valued. Just like Japanese

swords or tools used for tea ceremony or paintings, expensive Kimonos

are made by expert technicians - masters with long experience and highly

evaluated by people. You may think that Kimonos are like paintings made

by renown painters.

Some of these masters have been awarded with national prizes.

Young people buy cheap Kimonos or use rental systems.

If you go and search the internet, you may find Japanese sites for

buying or renting Kimonos.

College or high school girls often wear these types

of Kimonos which are not expensive. Most of them may cost you 20,000 -

30,000 yen when you buy them.

But in the case of formal Kimonos together with Obi body bands, perhaps

they may cost you more than 100,000 yen. or 50,000 in the cheapest case.

We’ll show you some examples of kimonos that are are

usually worn by college students. So, these clothes are not expensive,

but a rental system is often used by young people because they wear

Kimono only on some special occasions.

In this type of Kimono, students wear Kimono ( upper jacket ) along with

Hakama ( trousers ).

Usually they wear traditional sandals when they wear

almost all types of Kimono clothes. But in the case that they wear

Hakama trousers ( skirt ) along with Kimono, they sometimes wear Western

types of shoes or boots.

In such occasions as a graduation ceremony and the

subsequent party, not only college students but also teachers wear

Kimono.

K

I

M

O

N

O |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

zori |

zori |

tabi |

Japan, 2011 S.Y.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

tenno

TENNO

The Japanese word 'Tenno' by which the monarch of Japan has been

called, is an honorific title of 'Emperor'.

The first person who used this word is considered to be Prince-Regent

Shotoku (574-622), an ardent believer in Buddhism. That is probably why

he intended to rule the country as a boddhisattva.

What is the meaning of this?

An explanation:

The term "bodhisatta" (Pāli language) was used by the

Buddha in the Pāli canon to refer to himself both in his previous lives

and as a young man in his current life, prior to his enlightenment, in

the period during which he was working towards his own liberation. When,

during his discourses, he recounts his experiences as a young aspirant,

he regularly uses the phrase "When I was an unenlightened bodhisatta..."

The term therefore connotes a being who is "bound for enlightenment", in

other words, a person whose aim is to become fully enlightened.

Prince-Regent Shokotu was seeking enlightenment, not only for himself,

but also for others.

During his regency, he sent the first envoy to Sui China. The Sui

Dynasty (581-618 CE) was an ephemeral Imperial Chinese dynasty which

unified China in the 6th century.

According to The Chronicles of the Sui Dynasty, the letter sent in 607

by Prince-Regent Shokotu to the Emperor Yangdi began: "The Ruler of the

Land of Sunrise sends his message to the Ruler of the Land of Sunset."

To

the Chinese Emperor, who regarded himself as the supreme ruler of the

universe, this tone of equality and the contrast between Sunrise and

Sunset sounded like the height of insolence. In his reply, therefore,

the Emperor wrote at the opening, intending to show how the

Prince-Regent should address him: "The Emperor speaks to the Prince of

Yamato." (The Yamato period is the period of Japanese history when the

Japanese Imperial court ruled from modern-day Nara Prefecture, then

known as Yamato Province. Yamato = Japan, in this case.) To

the Chinese Emperor, who regarded himself as the supreme ruler of the

universe, this tone of equality and the contrast between Sunrise and

Sunset sounded like the height of insolence. In his reply, therefore,

the Emperor wrote at the opening, intending to show how the

Prince-Regent should address him: "The Emperor speaks to the Prince of

Yamato." (The Yamato period is the period of Japanese history when the

Japanese Imperial court ruled from modern-day Nara Prefecture, then

known as Yamato Province. Yamato = Japan, in this case.)

But the Prince-Regent, who insisted on terms of equality, ignored this

and just wrote in his next letter to the Chinese Emperor: "The Tenno

(the Ruler of the Heaven) of the East speaks to the Emperor of the

West."

Chinese Emperors and Japanese Tennos were totally different in function.

Successive Tennos reigned, but didn't rule. The actual ruler could be a

brother, regent, or shogun.

And, also interesting, in ancient times, there were several female

Tennos as well.

Empress Michiko, source:

http://www.navy.mil/view_single.asp?id=25793

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Modern art

MARIKO MORI

Mariko Mori lives and works in New York. Oneness is an

allegory of connectedness, a representation of the disappearance of

boundaries between the self and others. It is a symbol of the acceptance

of otherness and a model for overcoming national and cultural borders.

It also is a representation of the Buddhist concept of oneness, of the

world existing as one interconnected organism.

Little

is known about the personal life of Mariko Mori. She is believed to been

born in Tokyo in to be married to the composer Ken Ideka.

The artist graduated from the Bunka Fashion College (Tokyo) in 1988 and

spent most of her teenage years working there as a fashion model. Later

that year, feeling restrained by the Japanese ethic of uniformity, she

moved to London attending the Byam Shaw School of Art (1988-89), and

Chelsea College of Art, London (1989-92). Since she studied on an

Independent Study Program at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New

York (1992-93), Mariko continues to work and live both there and in

Tokyo.

The avant-garde artist Mariko Mori combines pop art, self-portraits,

modern technology and Buddhist ideologies in her art. Post-modern

Cyberfeminism, futuristic images, you can get it all, visiting one of

her exhibitions.

In her early self-portraits (photos) she shows herself in the female

roles in her native Japan: the official lady, the schoolgirl, the

prostitute. She is not a “normal” woman, however, but she shows herself

as a cyborg, a kind of robot, mechanical and sexless. As we can’t escape

the advancement of technology we must embrace it and use it…

"We've

fallen into a fin-de-siecle period of crisis in which people believe

only the things they see right in front of them" - Mariko Mori -

The cyborgs are developing, they become less human. As Mariko makes

videos, we can watch the more alien-like cyborgs moving, dancing. The

titles of her works are pessimistic in tone. They are warning us of

mappo, the dark period of moral decline before the arrival of the

future Buddha. This moral decline is due to a mixture of consumerism and

advanced technology. Mariko is not only pessimistic, because she has an

answer. She combines technology with traditional Buddhist beliefs.

On the exhibition in Groningen there are four panoramic colour

photographs, called Esoteric Cosmos (1996-98), with the names

Entropy of Love, Burning Desire, Mirror of Water and Pure Land.

They symbolise the four elements of nature as defined by Buddhist

teaching. Mariko transforms human images in a strange landscape, a kind

of utopian world.

One of the examples of her videos you can watch is Miko no Inori.

Mariko is outfitted entirely in white, looking like an alien, caressing

a crystal ball in her hands. In the meanwhile Mariko’s voice can be

heard, singing.

A

very impressive

project of hers is the “Wave UFO”. Only recently has technology

advanced far enough to be able to realize this work of art. Now the

audience can utilise their own brain activity …

I think

all kinds of fantasy and dreams are very important to our life.

(Mariko interviewed by Blair 1995).

For a short video impression of the exhibition, have a look at:

http://www.cedargallery.nl/engother_artists.htm

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

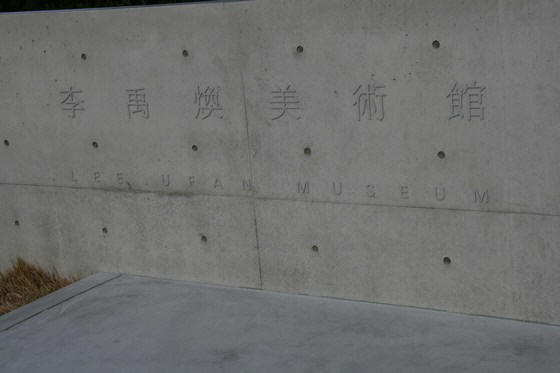

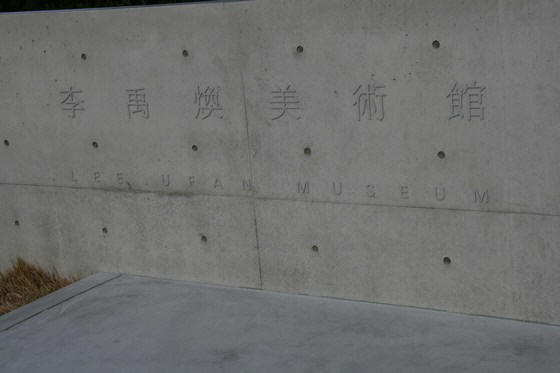

LEE UFAN

Naoshima, Lee Ufan museum

Naoshima, Japan, houses a lot of interesting spots.

One of these is the Lee Ufan Museum. A museum resulting from

collaboration between the internationally acclaimed artist Lee Ufan,

presently based mainly in Europe, and the architect Tadao Ando.

The Ando-designed semi-underground structure houses

paintings and sculptures by Lee spanning a period from the 1970s to the

present day. Lee's works resonate with Ando's building, giving visitors

an impression of both stillness and dynamism. Positioned in isolation in

a valley surrounded by mountains and sea, the museum offers a harmony

between nature, architecture, and art, where visitors is offered an

opportunity to return to their original natures and to find time for

quiet reflection in a society overflowing with material goods.

“I prefer an open relationship of encounter between

inner and outer phenomena to a completed, autonomous text. A work of art

can neither become an idea as such nor reality as such. It exists

between idea and reality, and ambivalent thing that is penetrated by,

and influences, both.

My work differs from the making of modernist

totalities or closed objects. It is important to create a stimulating

relationship between what I paint and what I do not paint, what I make

and what I do not make, the active and the passive.

By adding slight (one, two ot three) touches to the

canvas with ahnd, brush and paint, reverberating empty space is created

where paint is not applied.

….

It is human to live with dreams of transcendence.

Therefore, artistic expression should lead to reflection and leaps of

imagination. Just as human beings are physical beings, a paint of

contact between inner and outer worlds, works of art must be living

intermediaries that mediate between and exalt the self and the other."

Lee Ufan, Paris, 1999

Lee Ufan’s sculptures and paintings are austere,

minimal, and not all that easy for westerners to ‘comprehend’. It is

pervaded with a life view abd a way of looking at art that are quite

different from what westerners are used to. To Ufan Lee, things and in

particular objects from nature are phenomena, parts of a limitless

whole.

He endorses the statement of Tao Chuang-tzu, an influential Chinese

philosopher who lived around the 4th century BC:

‘Wood and stone are wood and stone and at the same time not wood and

stone, and that is why wood and stone are essentially an inconceivable

universe.’

The central theme of Lee’s work, then, is infinite space or infinity

itself.

Lee Ufan seeks a moment of silence and insight, and wants to offer it to

others.

Het writes:

‘Stand still a moment. Boisterous, busy people, stop and stand still

for just a moment. Look at the blue sky. Close your eyes and take a deep

breath. Do only this, and you will change and the world will come to

life.’

Come and take a look at his works in New York, Paris,

London. Or in Japan, of course.

photos naoshima © wagenvoorde

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

ISAMU WAKABAYASHI

An interesting artist, about who I unfortunately can't find

much information. One thing is clear, however. Nature is important for

him. He can see a tree as something equal to himself. He observes nature

with attention and love.

This is a Japanese approach. Take the Sakura trees, for example, with

their beautiful blossoms. Japanese people enjoy viewing their blossoms

very much.

And in Japan there are many old trees. Some Japanese people believe(d)

that gods should abide in such old trees. It is interesting to see how

the Japanese take care of these old trees.

There was an exhibition in Kröller Müller Museum in The Netherlands, in

2001, and this is a fragment of a quote of Isamu in their catalogue.

'Otterlo Mist

Being beside a walnut tree, I once tried to

approach the time that the tree had lived. That was the minimum work, I

continued for a few years. The labour accompanying this work provided me

with something and deprived me of something.

Now I have interest in another tree, a beech tree

in the forest of Otterlo. Behind this tree stand also a large number of

trees and there might be a certain possibility to contemplate and

imagine all sorts of affairs and lives related. Even though this forest

was artificially brought into existence, it seems now to have built up a

world where natural and botanical features are more remarkable. I admire

the exquisite form of the beech tree, but at the same time, I have to

become conscious of my position and limitation. By the side of this

tree, I attempt to keep a record of a tree and its background.

....'

Isamu Wakabayashi

Dec. 2000

(source: Catalogue Kröller Müller

Museum Otterloo 2001)

Otterlo Mist

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

More information about these, or other, artists, more pictures of

works of art are very welcome!

cedars@live.nl

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Prints

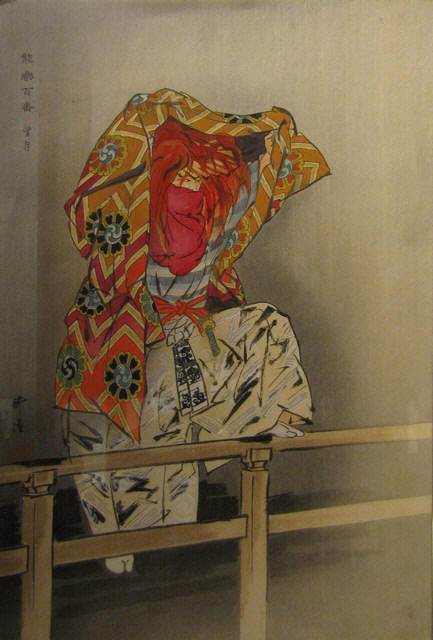

Japanese Nõ and Nature PRINTS BY TSUKIOKA KÕGYO

Tsokioka Kõgyo was born in Tokyo, on 18 April 1869

(under a different name). He studied painting at the Painting School of

Tokyo Prefecture and started his career by decorating porcelain. In

1887, he became a pupil of his stepfather, the illustrious printmaker

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892). In 1889, he went on to study with Ogata

Gekkõ (1859-1920), a renowned printmaker and painter in the Nihonga

style. Kõgyo made his first prints and paintings around 1890.

Kingfisher

At the beginning of Kõgyo’s career, his prints were mainly in

traditional genres, such as landscapes, flowers and birds.

Photo: Wagenvoorde

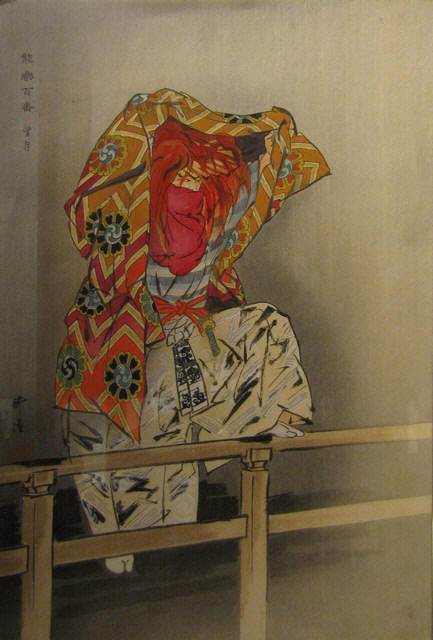

From 1897, his focus turned to the Nõ theatre. In his three big Nõ

theatre series, Picture of Nõ Performances (Nõgaku zue), One Hundred Nõ

Dramas ( Nõgaku hyakuban) and a Great Collection of Nõ Pictures (Nòga

taikan), Kõgyo made over five hundred prints altogether. These prints

give a colourful impression of the most important scenes and characters

from many theatre pieces, most of which are still performed today.

Photo: Wagenvoorde

The year of Tsukioka Kõgyo’s birth, 1869, coincided

with great political and economic upheaval in Japan. From 1603 to 1868,

the ‘shoguns’ had held sway over a feudal power system, controlling all

the distinguished families in Japan.

The emperor’s power was restored in 1868, at the start of the Meiji

period.

Emperor Meiji differed from the shoguns in his interest in the West,

including Western art. The modernization of Japan went hand in hand with

the rise of a strong nostalgia for the country’s own past and for

oriental values.

Kinsatsu from the series Nõgaku hyakuban, 1923

Photo: Wagenvoorde

Nō Theatre

One of these oriental values, the classical and subdued Nō theatre, had

thrived for centuries under Shogun rule and initially looked like

becoming a victim of the modernizations. It recovered, however, by

successfully convincing a new audience of its silent beauty. Nō theatre

dates from the 15th century as has build enormous prestige throughout

the years in Japan, Europe and the United States. The Nō theatre is a

theatrical form which was always abandoned from any historical place or

date. It's a more autonomous theatre form in which spiritual elements

are very important. Not only on stage, but also on printed paper Nō

theatre was and is an enormous success.

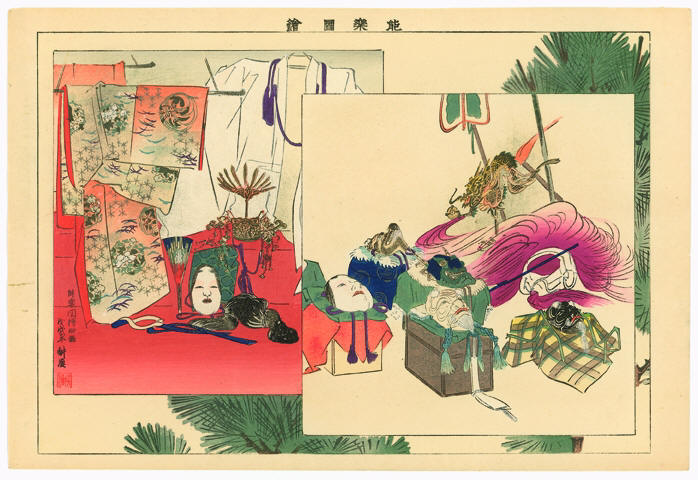

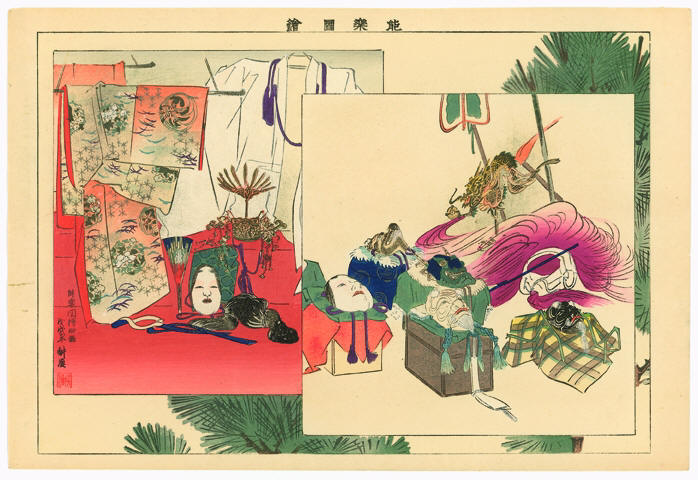

Picture of a Nõ Theatre, 1898

The prints from Kōgyo give a lot of information about

the plays (often showing an important scene from the story), as well as

the situations backstage. There are also prints of singers and

musicians, props and masks, and the construction of the stage itself.

Left: ?

Right: Nõ Masks from the series Nògaku zue, ca. 1900

Photo: Wagenvoorde

At the time of Kõgyo’s death in 1927, the Nõ theatre

had gained a strong position in the performing arts and was popular with

a steadily growing Japanese audience. Kõgyo’s work reflects this

enthusiasm for the beauty and elegance of the Nõ theatre at the heart of

the Japanese tradition.

Photo: Wagenvoorde

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

More information about these, or other, artists, more pictures of

works of art are very welcome!

cedars@live.nl

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Glossary

fukusa - silk cloth used by tea masters to

wipe utensils during tea ceremony

geisha - (lit. person of the arts')

professional female entertainer or companion

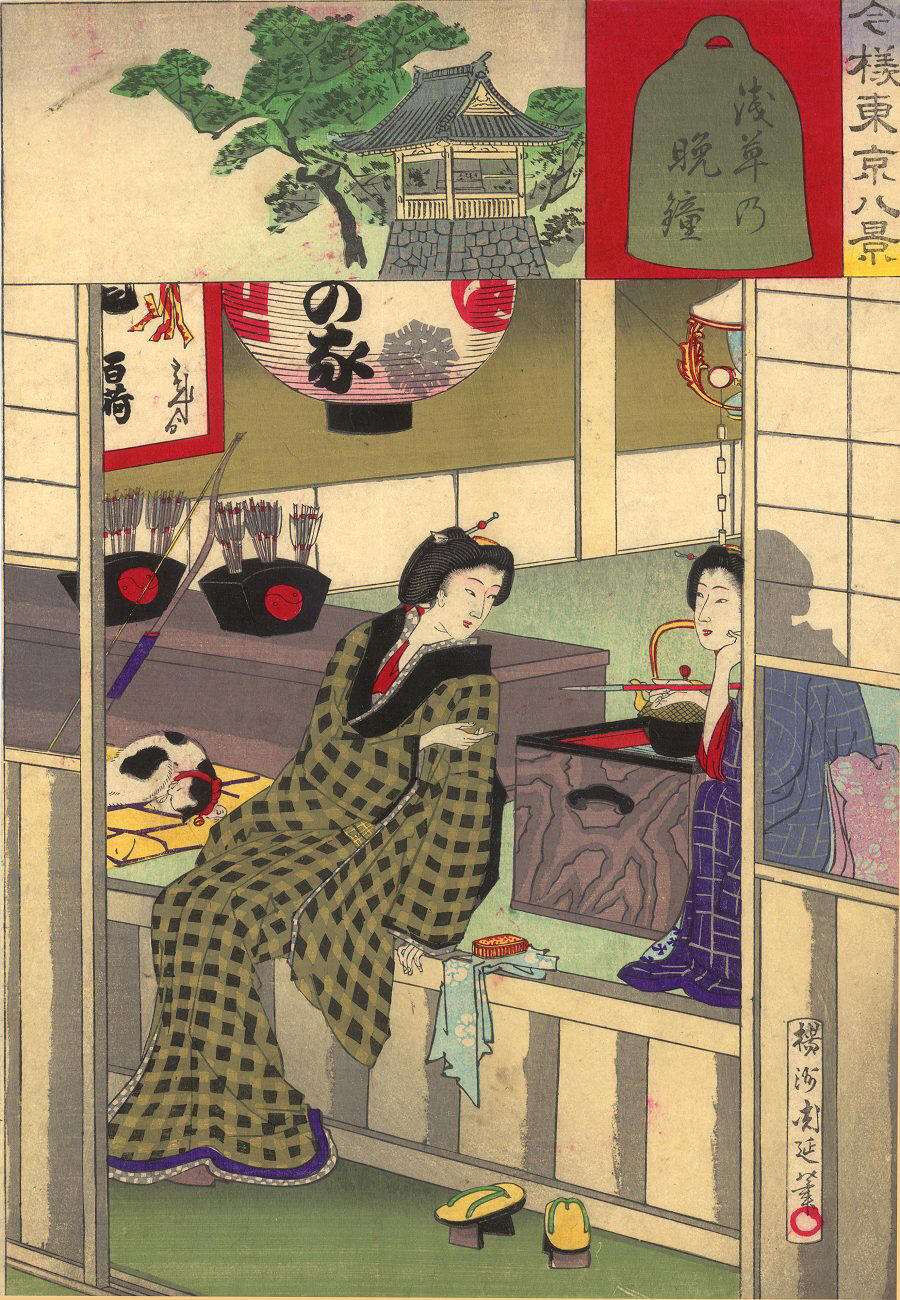

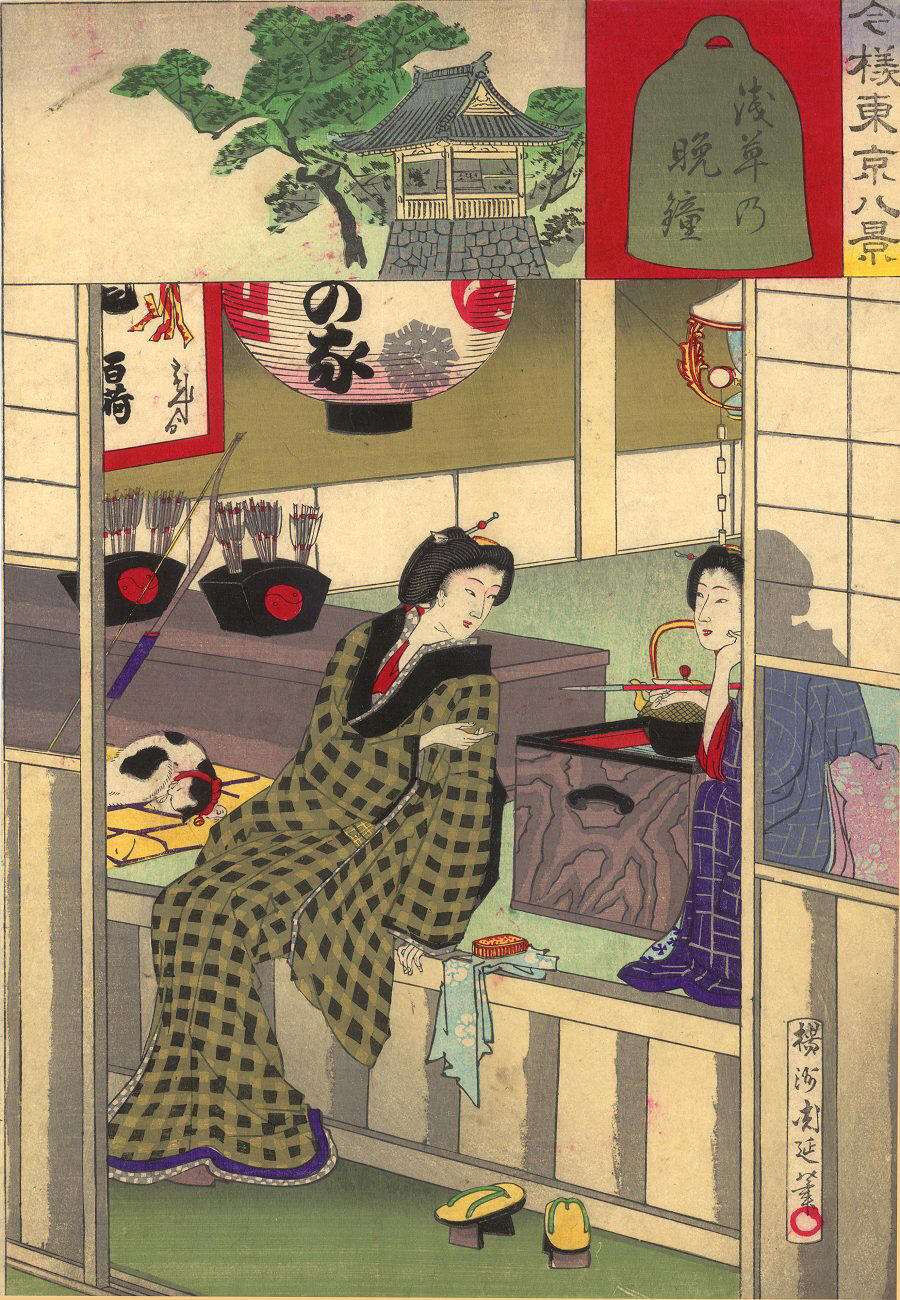

Two geishas relaxing after having entertained; the insets showing

the curfew bell at Asakusa.

Ukiyo-e woodblock print by Yōshū Chikanobu, 1888

geta - traditional wooden clogs

haiku - seventeen-syllable poem (http://www.cedargallery.nl/engjapan_poetry.htm)

ikebana - traditional art of flower

arrangement

Jizo - Jizō is

popularly venerated as the guardian of unborn, aborted, miscarried, and

stillborn babies

Jizo

©wagenvoorde

Kabuki - form of traditional Japanese theater

characterized by elaborate costumes, stylized acting and the use of male

actors for all roles

kaomise - (lit. 'face showing') performance of Kabuki held in

Kyoto in December, featuring leading Kabuki actors

katsu - meaningless shout, used in Zen to shock or surprise and

thereby lead to enlightenment

koan - illogical Zen Buddhist riddle, used as a meditational tool

to achieve enlightenment

koto - thirteen stringed musical instrument

kuruwa - enclosures or walled areas within a city, which were

inhabited by courtesans

Matcha - also maccha, refers to finely milled

or fine powder green tea. The Japanese tea ceremony centers on the

preparation, serving, and drinking of matcha

men - (lit. 'face') front of an object

mu - concept of 'nothingness' which lies at the core of Zen

onnagata - male actors who play women's roles

in Kabuki

pachinko - gambling game played on a vertical

pinball machine

seidan - term originating in fourth-century

Taoist gatherings: the art of 'pure conversation'

Shinto - polytheistic indigenous religion of Japan (http://www.cedargallery.nl/engjapan_religion.htm)

Shinto

©wagenvoorde

suki - playful architectural style which focuses on details,

strongly influenced by tea ceremony

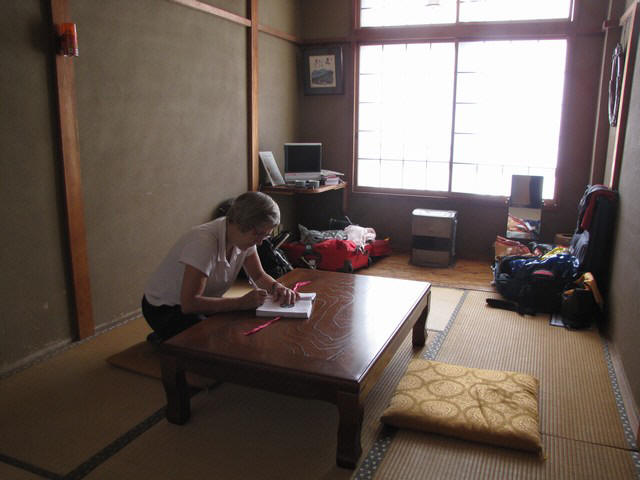

tatami - woven floor matting, used as a unit

of room measurement

tatami on the floor

©wagenvoorde

tatebana - formal style of ikebana known as 'standing flowers'

tokonoma - decorative alcove found in most Japanese homes in

which flowers, a scroll or other artworks may be displayed

torii - entrance gate to a shrine

wabi - (lit. 'worn' or 'humble') emphasis on

simplicity and humble, natural materials. First incorporated into tea

ceremony, wabi has come to symbolize all that is

unostentatious in the traditional arts

waka - thirty-one-syllable poem

yago - actor's 'house name', which is shouted by members of the

audience at dramatic moments during a Kabuki play

yukata - summerweight cotton kimono

wearing a yukata

©wagenvoorde

Zen - Japanese school of Buddhism, introduced

in the twelfth century from China, which teaches the achievement of

enlightenment through inner contemplation

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

TOP * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Our website, and certainly the section about Japan,

is a labour of love.

The study of Japanese religions and religious art has expanded

greatly in the West over the past five decades, and one example you can

find here:

http://www.brill.com/portraits-chogen

Several books are written, several websites created.

Nevertheless we hope that our visitors enjoy what they find and read

here.

Our site is just a modest tribute to (the beauty of) Japan.

JAANUS is the on-line Dictionary of Japanese

Architectural and Art Historical Terminology compiled by Dr. Mary

Neighbour Parent.

An excellent recourse:

http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/

top |

previous

Texts, pictures,

etc. are the property of their respective owners.

Cedar Gallery is a non-profit site. All works and articles are published

on this site purely for educational reasons, for the purpose of

information and with good intentions. If the legal representatives ask

us to remove a text or picture from the site, this will be done

immediately. We guarantee to fulfill such demands within 72 hours.

(Cedar Gallery reserves the right to investigate whether the person

submitting that demand is authorized to do so or not).

The contents of this

website (texts, pictures and other material) are protected by copyright.

You are welcome to visit the site and enjoy it, but you are not allowed

to use it, copy it, spread it. If you like to use a picture or text,

first send your request to

cedars@live.nl

|

To

the Chinese Emperor, who regarded himself as the supreme ruler of the

universe, this tone of equality and the contrast between Sunrise and

Sunset sounded like the height of insolence. In his reply, therefore,

the Emperor wrote at the opening, intending to show how the

Prince-Regent should address him: "The Emperor speaks to the Prince of

Yamato." (The Yamato period is the period of Japanese history when the

Japanese Imperial court ruled from modern-day Nara Prefecture, then

known as Yamato Province. Yamato = Japan, in this case.)

To

the Chinese Emperor, who regarded himself as the supreme ruler of the

universe, this tone of equality and the contrast between Sunrise and

Sunset sounded like the height of insolence. In his reply, therefore,

the Emperor wrote at the opening, intending to show how the

Prince-Regent should address him: "The Emperor speaks to the Prince of

Yamato." (The Yamato period is the period of Japanese history when the

Japanese Imperial court ruled from modern-day Nara Prefecture, then

known as Yamato Province. Yamato = Japan, in this case.)